Can open-source solar cooker designs deliver performance?

by SCI Youth Volunteer, Arun Raman

My best source for open-source solar cooker designs was the SCI wiki[1]. Although there are numerous open source designs available online, the challenge I faced was narrowing my selection. To tackle the problem of deciding which solar cooker model to build, I came up with a series of guidelines: I would build one of each type of solar cooker (parabolic, box, and panel) and choose the most affordable and simple model to build. An inexpensive solar cooker is more accessible to the public while a simple cooker is easy for even the most inexperienced to build. I wanted the solar cooker designs I chose to be straightforward and inexpensive for anyone to make. The models I chose were the Parvati parabolic cooker, Minimum Solar Box Cooker, and Fun-Panel Cooker.

Building the cookers was not as simple as I first expected it to be. Sourcing the necessary materials—mainly cardboard, aluminium foil and glue—to build the cooker for as low of a cost as possible was anything but easy. Luckily, my neighbours happened to be moving and so they permitted me to take their extra cardboard boxes. I ran into a problem with those boxes, however, as they were smaller than the required size for my chosen designs. To resolve this issue, I had to glue multiple boxes together in order to have enough cardboard. In addition, some of the cardboard pieces had to be precisely folded in order to take a curved shape. I solved this problem by using a ruler to make creases in the cardboard and folded along those creases. Finally, to glue the aluminium foil, which acted as a reflective material, onto the cardboard, I made a liquid glue from mixing non-toxic glue with water. Before testing, I had to calculate aperture area, a parameter necessary for testing, as none of the open-source designs provided that info. Calculating it was one of the most difficult parts of my experience.

The first cooker I built, the Parvati cooker, performed very poorly, struggling even to cook an egg in reasonably fair weather. I chalked up its poor performance to its small size and the fact that it was the first cooker I had ever built, meaning there may have been some error. While the first cooker was not successful in my eyes, the Fun-Panel cooker was excellent, rivalling the performance of commercial cookers for close to free. I was able to cook eggs, rice, potatoes, and even lentils in no time at all. My box cooker was just as successful.

After cooking multiple times, I wanted to put my open-source cookers to the rigorous testing standards of ASAE[2]. Under Dr Bigelow’s guidance, I was able to take advantage of SCI’s testing facilities. We tested both my Parvati and Fun-Panel cooker with encouraging results. I plan to continue to build, test and to publish the results.

Hopefully, the publication of my testing results will allow the improvement of current open source designs in cooking efficiency. Additionally, it can act as a catalyst for convincing more commercial solar cooking companies to test their cookers using SCI’s performance evaluation process. At this point, few open source solar cookers and even fewer commercial cookers have been tested according to a standard protocol. By standardizing results, existing solar cookers can be ranked based on performance metrics in order to choose the best cooker for consumers and for distributing to those in need. Furthermore, the fact that an open source cooker could compete performance-wise with a commercial one demonstrates that it is not mandatory to spend money to have a viable cooking experience.

Testing my solar cookers with Dr Alan Bigelow at Solar Cookers International was a great experience and I look forward to continue working with him and SCI.

Testing with Dr Bigelow

[1]http://solarcooking.org/plans/default.htm?redirect=no

[2]https://vignette.wikia.nocookie.net/solarcooking/images/f/f9/ASAE_Standard_S580.1_%28Nov_2013%29.pdf/revision/latest?cb=20150721205417

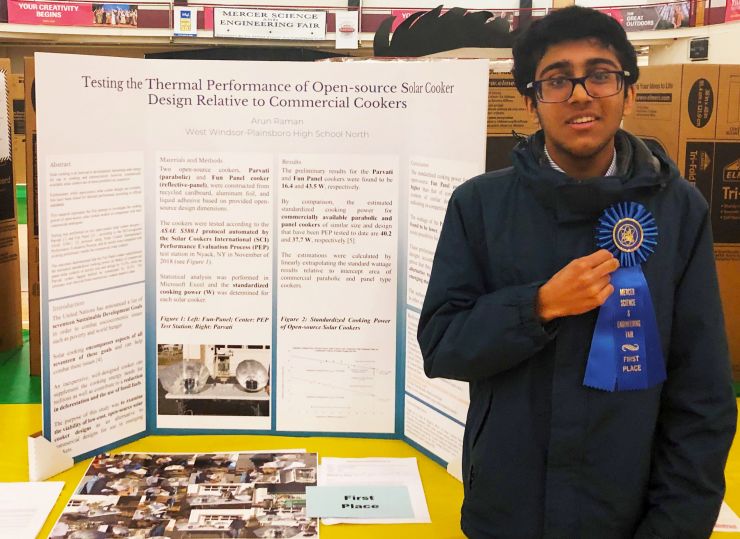

Update on Arun

Congratulations to SCI Volunteer Arun Raman on receiving first place in the field of energy for “Testing the Thermal Performance of Open-source Solar Cooker Design Relative to Commercial Cookers” at the Mercer Science and Engineering Fair. SCI is pleased to build capacity and research with the next generation of scientists and solar cooks.